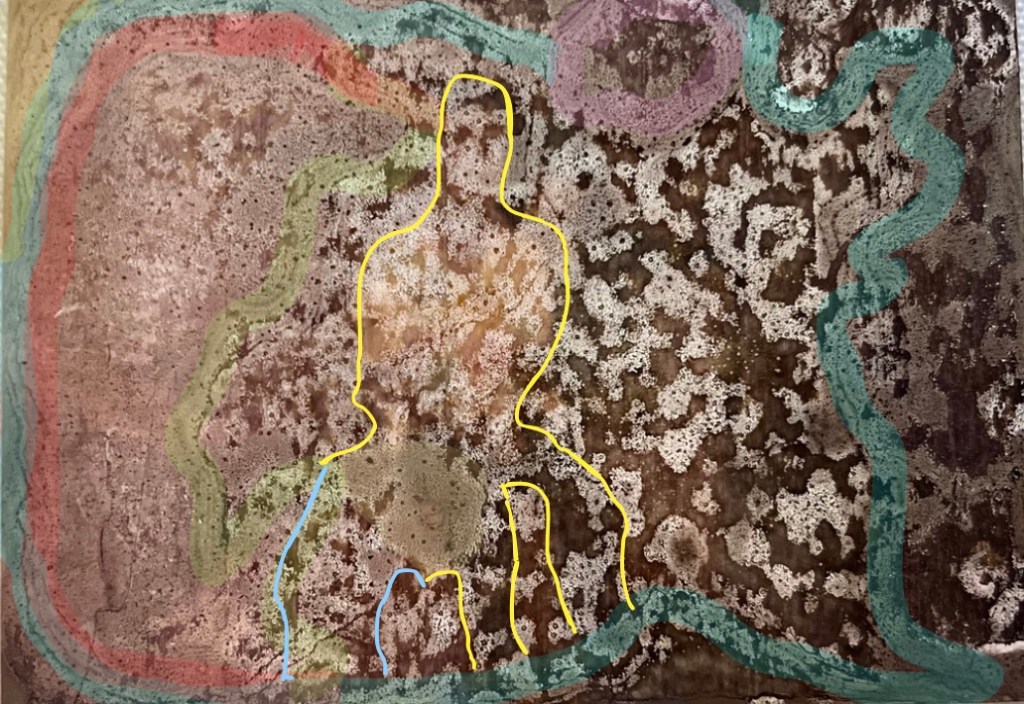

Image 1 : Unidentifiable photograph covered by fungal mould from the collections of Jiugailiu and Gaikhuanlung Gangmei. (Lines drawn by author to trace and make sense of figures the image used to hold)

“Sireiliu Photo Pang Akho tad bamme” 1 (“Sireiliu is going around asking and collecting photos” ) is an endearing refrain that encircles me whenever I go back to the field, the field being Tamenglong town, the district headquarter of Tamenglong dsitrict, Manipur : the subject of my fixed interest for five years. It has been 5 years of Akha (asking, collecting) and Akhom (collecting, bringing together) of photographs, and each year I find myself ever so lost, still so curious and deeper deeper into the forest of the incomplete.

There is this thing that is true and one can only experience it to know that it is true, this thing is not grounded in science, it sounds irrational so it is best understood as a common superstition. This truthful superstition is that if you so much as see a hairy caterpillar, without even touching it, you will find yourself covered in rashes by nightfall. Much like this thing, there is another thing that I consider true – it is the experience of the fungus, expanding their territories of mould in my brain, after seeing the resin coating of photographs being eaten away by the same fungus to make new homes for themselves. This fungus alone cannot be blamed for the state of my mind; one could also accuse the encumbrance of the Archive. ‘I’ might also be the only reason of blame. Still, all of this has been necessary, it has taught me to approach the process of ‘Khom Ndui’ which shall be made clear as you keep reading, with a careful and tender sort of vigilance that I would not have known five years ago. Khom Ndui, as how i see it, can work as a salve to repair the consequences of experiencing a thing or in the town’s case a number of things. The experience of this thing is unconvincing for anyone except for the people within a region that has always been at the mercy of and transferred from one extractive empire to another.

To give a flattened response, yes, this project is an attempt at archiving photographs to aid the multiple oral and written histories of the town and to perhaps help museumise these histories but to give an answer less obedient to the language and frameworks of the mainstream, this project, at least for now, refuses to be an archive. If later, the need arises to assume that role, then it is for my people to decide. I must also tell you, readers, that who I refer to as “my people”, are the four kindred tribes; Zeme, Liangmai, Rongmei, and Inpui, the four communities who inhabit the district headquarter.

I call this project a practice because it must remain in motion, to be corrected if it grows stagnant, to adapt as times and circumstances change. It can be understood as being equivalent to the concept of the “anarchive”2, it is not an outright refusal, it can take shape to allow people to call it an archive. I guess, it is an organism, though one I imagine very differently from the often repugnant visual interpretations of Deleuze and Guattari’s “rhizome.”

The refusal to call it an archive comes from the truth that archives have always felt unfriendly to me. I have never found one where I felt represented. Besides, this collection does not claim authority, much less the weight of a state-sanctioned method of museumising, in defining the multiple truths and histories that the place carries. Representation for people who are constantly asked to explain their identity, even to peers from the same so-called marginal, neglected region, is fraught. It only acts as a state-sanctioned method of estrangement for those who exist at the margins of South Asian de-colonial discourses, for those who live in fear of the Indian state’s imaginings, for those whose presence is almost non existent in Manipur’s public memory, and for those who are abandoned in the writings of the ‘Naga’ struggle for self determination . So, the idea of an archive, or any authority assuming the role of a sanctioned history-making institution, feels all the more hostile for people already existing under different forms of violence. Has the state, or any nation-state, ever asked the publics, all the different ones, especially those left out of public memory making, if they would like to be included?

The town of Tamenglong does not maintain or possess an archive, and the visual history of the town is fading from collective memory. The people who lived when the town began with all of its firsts are forgetting details and traces of the photographs they took. This urgency, the fear of forgetting, is what forces me to crawl out of the moulds for the collection I now hold to find meaning and purpose beyond an academic project. Allow me, for now, to ignore the recent debates around preservation and conservation. I promise to return to them once this practice becomes an ‘archive’.

There is a need, and there is an urgency, and there is a need to be urgent about the preservation of photographs. I call this project Khom Ndui, – a kinetic phrase made of two active verbs. I chose this phrase after asking and collecting words from my dear friends, seniors and my parents for common words and phrases shared across the Zeme, Liangmai, Rongmei, and Inpui languages. The meaning of Khom Ndui is difficult to be pinned down and translated. When I think of ‘Akha’, ‘Akhom’ and ‘Ndui/Madui’, I visualise the words as constant but gentle and patient movements, much like the ushers in church handing the ‘offering bag’ to collect our offerings and oh, how perfectly it defines the practice I wish to practice.

Khom Ndui, “collecting, bringing together” of people, of things, of photographs. The practice is this, to acknowledge that I have been asking, pestering, and collecting these photographs, but also to insist that this collection cannot be in vain. The collection must activate something, a practice of gathering, seeing, reading, and studying photographs. Most importantly, it must remain open to more contributions, with text and stories supplementing the images.

What then is my role in all of this collecting and knowledge dispensing business? I guess, I see myself as somewhat analogous to that of a church caretaker : holding the keys, taking care and keeping the collection safe. This role is not permanent and will eventually be passed on. And so, one can understand the space this collection activates, like that of our local tribal churches, a space for people to come together, to share, reflect, and learn, but without the formal structures of a deacon board or other authorities.

Helping my people understand what it is I actually do has been pivotal in shaping the purpose of this collection. No, I have never asked the collection itself what it wants, because the region has not yet reached a point of academic saturation or finality where we feel compelled to grant agency to the inanimate.

In the courts of my people, here is the case I always make for the importance of the family album; I begin by showing photographs (see Image 1), devoured by fungus, as all photographs will eventually be in the sub tropical rain forest of Tamenglong district if left uncared for. The black-and-white prints on fiber based paper are at risk of disappearing altogether (see Image 3). Some pages show only the marks of photographs once pasted there, now stolen or missing (see Image 2). Some us may know all too well, the vain effort of shifting our family albums to to Imphal to prevent destruction, only for them to meet the tragic fate of being drowned in the capital’s monsoon floods.

The family album is not just a source to dig out “fascinating” micro-histories of families in silos. I see the family album as an unassuming repository, unaware of its own powers to disrupt existing archives, that quietly holds safe a constellation of images, snapshots, witnesses, and absences which the townspeople continue to remember in their oral tales. The photographic evidences of the town’s history, its changing landscape, lies hidden in the family albums of those who have allowed me to look through.

And so I end here for tonight, the first diary entry/ notes from the field of this project to try and convince no one else but my people, to join me in this journey of Akha, Akhom.

My gratitude to the following people for helping me with translations : Asangle Disong and Ingauzeule Kenrang for Zelet, Lozaan Khumbah and Jianthui Bariam for Inpui choung, Achi Wichamdin Mataina for Lianglad and Lois Panmei for Ronglat

- The phrase is in Ronglat and it means “Sireiliu is going around asking and collecting photos” ↩︎

- See Springgay, S., Truman, A., & MacLean, S. (2019). Socially Engaged Art, Experimental Pedagogies, and Anarchiving as Research-Creation. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(7), 897-907.Massumi,

B. (2016). ‘Working Principles’, in The Go-To How To Book of Anarchiving, ed. by A. Murphie. (pp. 6–8). The SenseLab, http://senselab.ca/wp2/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Go-To-How-To-Book-of-Anarchiving-Portrait-Digital-Distribution.pdf

↩︎

Leave a comment